Potassium disorders are commonly encountered in clinical practice. They are important because of the role potassium plays in determining the resting membrane potential of cells. Changes in plasma potassium mean that ‘excitable’ cells, such as nerve and muscle, may respond differently to stimuli. In the heart (which is largely muscle and nerve), the consequences can be fatal, e.g. arrhythmias.

Serum potassium and potassium balance

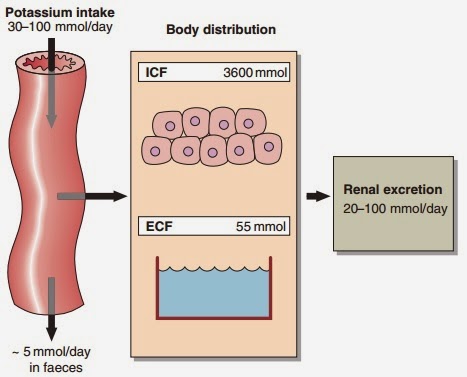

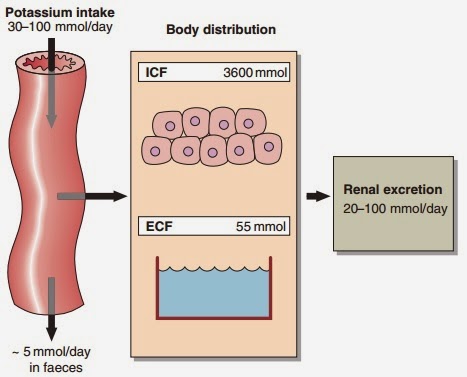

Serum potassium concentration is normally kept within a tight range (3.5–5.3 mmol/ L). Potassium intake is variable (30–100 mmol/day in the U K) and potassium losses (through the kidneys) usually mirror intake. The two most important factors that determine potassium excretion are the glomerular filtration rate and the plasma potassium concentration. A small amount (~5 mmol/day) is lost in the gut. Potassium balance can be disturbed if any of these fluxes is altered (Fig 11.1). An additional factor often implicated in hyperkalaemia and hypokalaemia is redistribution of potassium. Nearly all of the total body potassium (98%) is inside cells. If, for example, there is significant tissue damage, the contents of cells, including potassium, leak out into the extracellular compartment, causing potentially dangerous increases in serum potassium (see below).

Hyperkalaemia

Hyperkalaemia is one of the commonest electrolyte emergencies encountered in clinical practice. If severe (>7.0 mmol/L), it is immediately life-threatening and must be dealt with as an absolute priority; cardiac arrest may be the first mani- festation. ECG changes seen in hyperkalaemia (Fig 11.2) include the classic tall ‘tented’ T-waves and widening of the QRS complex, reflecting altered myocardial contractility. Other symptoms include muscle weakness and paraesthesiae, again reflecting involvement of nerves and muscles.

Hyperkalaemia can be categorized as due to increased intake, redistribution or decreased excretion.

|

| Fig 11.1 Potassium balance |