This heterogeneous group of conditions is associated with monoclonal immunoglobulin in serum or urine, and is characterized by disordered proliferation of monoclonal lymphocytes or plasma cells. The clinical phenotypes of these conditions are determined by the rate of accumulation, site and biological properties of both the ab- normal cells and the monoclonal protein.

Tuesday, January 20, 2015

Monday, January 19, 2015

The Myelodysplastic Syndromes

Introduction

• The myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) are a group of clonal haemopoietic disorders. They are characterized by:

• Ineffective haemopoiesis resulting in peripheral blood cytope- nias of all three lineages, but especially anaemia

• Increased risk (30%) of transformation to acute myeloid leukaemia

• MDS is mainly a disease of the elderly, with a median age at diag- nosis of 60–75 years. It does, however, affect younger adults also. MDS is rare in children, and is associated with genetic disorders such as Fanconi’s anaemia.

Sunday, January 18, 2015

Quality assurance in the laboratory

Quality assurance in the laboratory includes all aspects of the analytical work, from correct identification and preparation of the patient to ensuring that the laboratory result goes back to the doctor.

The prime objective of quality assurance is to ensure that the laboratory provides results that are correct and relevant to the clinical situation of the patient.

Safety in the laboratory

● Each laboratory should have a written manual of safe laboratory practices which should be followed at all times.

● The laboratory should have a first-aid box (see section 3.8.2) and at least one staff member trained in first aid.

● The laboratory should be a work area only; visitors should be restricted.

● No food or drink should be consumed in the laboratory.

● Wear protective clothing and remove it before leaving the laboratory.

● Always consider any laboratory specimen as potentially infectious and handle it carefully; wear protective gloves.

Intravenous fluid therapy

Does this patient need IV fluids?

The easiest and best way to give fluids is orally. The use of oral glucose and salt solutions may be life-saving in infective diarrhoea. However, patients may be unable to take fluids orally. Often the reason for this is self-evident, e.g. because the patient is comatose, or has undergone major surgery, or is vomiting. Sometimes the decision is taken to give fluids intra-venously even if the patient is able to tolerate oral fluids. This can be because there is clinical evidence of fluid depletion, or biochemical evidence of electrolyte disturbance, that is felt to be severe enough to require rapid correction (more rapid than could easily be achieved orally)

Friday, January 16, 2015

Hypokalaemia

The factors affecting potassium balance have been described previously (p. 22). Hypokalaemia may be due to reduced potassium intake, but much more frequently results from increased losses or from redistribution of potassium into cells. As with hyperkalaemia, the clinical effects of hypokalaemia are seen in ‘excitable’ tissues like nerve and muscle. Symptoms include muscle weakness, hyporeflexia and cardiac arrhythmias. Figure 12.1 shows the changes that may be found on ECG in hypokalaemia.

Diagnosis

The cause of hypokalaemia can usually be determined from the history. Common causes include vomiting and diarrhoea, and diuretics. Where the cause is not immediately obvious, urine potassium measurement may help to guide investigations. Increased urinary potassium excretion in the face of potas- sium depletion suggests urinary loss rather than redistribution or gut loss. Equally, low or undetectable urinary potassium in this context indicates the opposite.

Reduced intake

This is a rare cause of hypokalaemia. Renal retention of potassium in response to reduced intake ensures that hypokalaemia occurs only when intake is severely restricted. Since potassium is

|

| Fig 12.1 Typical ECG changes associated with hypokalaemia. (a) Normal ECG (lead II). (b) Patient with hypokalaemia: note flattened T-wave. U-waves are prominent in all leads. |

Spirochetes and Bacteria without a Cell Wall

Spirochetes and bacteria without a cell wall do not quite fit in with the classic con- cepts of bacteria that have been discussed so far. It is also a fact that there is no similarity between the members of the two groups; they are very different from each other. They are discussed here in one chapter only for the sake of brevity.

SPIROCHETES

Spirochetes are spiral, Gram-negative bacteria with a unique mode of motility that is quite different from those of other bacteria (they lack external flagella). All bacteria classified as spirochetes generally have a helical protoplasmic cylinder made of a thin layer of peptidoglycan and a multilayered outer membrane. Spirochetes differ considerably from each other with respect to habitats and physiological characteristics. Three genera are associated with serious diseases in humans. These are Treponema, Borrelia, and Leptospira.

Treatment of Fungal Keratitis

MEDICAL THERAPY

The antifungal agents available today are mostly fungistatic, requiring a prolonged course of therapy. Although models of Aspergillus and Candida have been established, there are no reliable animal models of Fusarium keratitis. Fungi considered to be ocular pathogens are rarely encountered among the systemic mycoses. Thus, the therapeutic principles valid for systemic fungal infections may not apply to the cornea (O’Day DM 1987). In vitro antifungal sensitivities often are performed to assess resistance patterns of the fungal isolate. However, in vitro susceptibility testing may not correspond with in vivo clinical response because of host factors, corneal penetration of the antifungal, and difficulty in standardization of antifungal sensitivities.

Molecular-based Diagnostics for Ocular Fungal Infections

POLYMERASE CHAIN REACTION (PCR)

PCR is rapid diagnostic technique to detect the infectious agents even in small volume of samples. PCR is typically used for one of the following scenarios:

1. The patient presents with signs and symptoms that are most likely an infection but a definitive diagnosis cannot be made.

2. When a patient does not respond appropriately to therapy, or

3. For confirmation of a diagnosis when a patient or

4. When the patient's natural history does not coincide with his or her clinical presentation.

Tuesday, January 13, 2015

Miscellaneous Gram-Negative Bacteria

This chapter covers several Gram-negative but unrelated taxa. We did not mean to make this chapter a dumping ground, but they are all included in this chapter simply for the sake of brevity. The important taxa include the following:

• Brucella melitensis

• Bordetella pertussis

• Francisella spp.

• Pasteurella spp.

• Vibrio cholerae

• Campylobacter spp.

• Helicobacter spp.

• Legionella spp.

• Gardnerella vaginalis

• Chlamydia spp.

• Rickettsia rickettsii

Platelet Disorders

Platelets are small anucleate cells produced predominantly by the bone marrow megakaryocytes as a result of budding of the cytoplasmic membrane. Megakaryocytes are derived from the haemopoietic stem cell, which is stimulated to differentiate to mature megakaryocytes under the influence of various cytokines, including thrombopoietin. Platelets play a key role in securing primary haemostasis.

Once released from the bone marrow, young platelets are trapped in the spleen for up to 36 hours before entering the circulation, where they have a primary haemostatic role. Their normal lifespan is 7–10 days and the normal platelet count for all age groups is 150–450 × 10^9/L. The mean platelet diameter is 1–2 µm, and the normal range for cell volume (mean platelet volume; MPV) is 8–11 fL. Although platelets are non-nucleated cells, those that have recently been released from the bone marrow contain RNA and are known as reticulated platelets. They normally represent 8–16% of the total count and they indirectly indicate the state of marrow production.

Monday, January 12, 2015

The Acute Leukaemias

Acute leukaemia is a malignant disorder of white cells caused by a failure of normal differentiation of haemopoietic stem cells and pro- genitors into mature cells. This results in the accumulation of primitive leukaemic cells within the bone marrow cavity, causing bone marrow failure, and as a consequence patients typically present with anaemia, thrombocytopenia or neutropenia (Box 6.1).

Much progress has been made in understanding the pathogenesis of the acute leukaemias, and it is now clear that they occur because of the acquisition of distinct genetic abnormalities in haemopoietic stem cells or committed progenitors. These molecular abnormalities frequently occur as the result of chromosomal translocations or the loss of chromosomal material. In addition, activating mutations in genes regulating cellular proliferation, such as tyrosine kinase genes, are commonly identified. Malignant transformation of primitive cells with the capacity to develop into cells of the myeloid lineage results in acute myeloid leukaemia (AML), while acquired genetic

Thursday, January 8, 2015

Hyperkalaemia

Potassium disorders are commonly encountered in clinical practice. They are important because of the role potassium plays in determining the resting membrane potential of cells. Changes in plasma potassium mean that ‘excitable’ cells, such as nerve and muscle, may respond differently to stimuli. In the heart (which is largely muscle and nerve), the consequences can be fatal, e.g. arrhythmias.

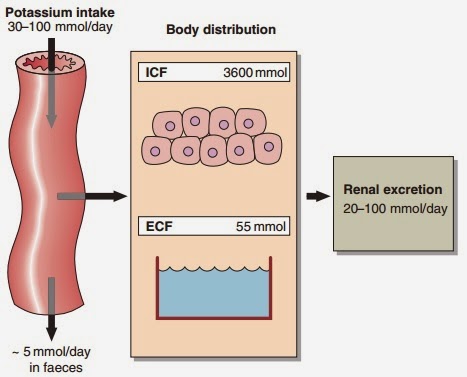

Serum potassium and potassium balance

Serum potassium concentration is normally kept within a tight range (3.5–5.3 mmol/ L). Potassium intake is variable (30–100 mmol/day in the U K) and potassium losses (through the kidneys) usually mirror intake. The two most important factors that determine potassium excretion are the glomerular filtration rate and the plasma potassium concentration. A small amount (~5 mmol/day) is lost in the gut. Potassium balance can be disturbed if any of these fluxes is altered (Fig 11.1). An additional factor often implicated in hyperkalaemia and hypokalaemia is redistribution of potassium. Nearly all of the total body potassium (98%) is inside cells. If, for example, there is significant tissue damage, the contents of cells, including potassium, leak out into the extracellular compartment, causing potentially dangerous increases in serum potassium (see below).

Hyperkalaemia

Hyperkalaemia is one of the commonest electrolyte emergencies encountered in clinical practice. If severe (>7.0 mmol/L), it is immediately life-threatening and must be dealt with as an absolute priority; cardiac arrest may be the first mani- festation. ECG changes seen in hyperkalaemia (Fig 11.2) include the classic tall ‘tented’ T-waves and widening of the QRS complex, reflecting altered myocardial contractility. Other symptoms include muscle weakness and paraesthesiae, again reflecting involvement of nerves and muscles.

Hyperkalaemia can be categorized as due to increased intake, redistribution or decreased excretion.

|

| Fig 11.1 Potassium balance |

Wednesday, January 7, 2015

Hypernatraemia

Hypernatraemia is an increase in the serum sodium concentration above the reference interval of 133–146 mmol/ L. Just as hyponatraemia develops because of sodium loss or water retention, so hypernatraemia develops either because of water loss or sodium gain

Water loss

Pure water loss may arise from decreased intake or excessive loss. Severe hypernatraemia due to poor intake is most often seen in elderly patients, either because they have stopped eating and drinking voluntarily, or because they are unable to get something to drink, e.g. the unconscious patient after a stroke. The failure of intake to match the ongoing insensible water loss is the cause of the hypernatraemia. Less commonly there is failure of AVP secretion or action, resulting in water loss and hypernatraemia. This is called diabetes insipidus; it is described as central if it results from failure of AVP secretion, or nephrogenic if the renal tubules do not respond to AVP. Water and sodium loss can result in hypernatraemia if the water loss exceeds the sodium loss. This can happen in osmotic diuresis, as seen in the patient with poorly controlled diabetes mellitus, or due to excessive sweating or diarrhoea, especially in children. However, loss of body fluids because of vomiting or diarrhoea usually results in hyponatraemia.

Dispatch of specimens to a reference laboratory

The peripheral laboratory sends specimens to reference laboratories or more specialized laboratories for examinations that cannot be carried out locally. For example, serological examinations for treponemal infection or typhoid; culture of stools for detection of cholera vibrio; and histological examination of biopsy material.

Table 3.2 shows, for each type of specimen and each examination:

— which container and preservative (where necessary) to use;

— how much of the specimen to send;

— how long the specimen will keep.

1. Packing specimens for dispatch

Always observe the regulations in force in your country.

Double pack specimens. Place the specimen in the bottle or tube and seal her- metically (fixing the stopper with sticking-plaster; see Fig. 3.73).

Check that the bottle is labelled with the patient’s name and the date of collection of the specimen. Then place the sealed bottle in an aluminium tube with a screw cap. Wedge it in the tube with absorbent cotton wool.

Wrap the request form around the metal tube (Fig. 3.74). It should show:

— the patient’s name (written in capital letters) and date of birth;

— the nature of the specimen;

— the date of collection of the specimen;

Disposal of laboratory waste

1. Disposal of specimens and contaminated material

Any clinical material brought into the laboratory and any apparatus used to handle this material must be considered as infectious. To avoid laboratory accidents, make sure that priority is given to correct handling and disposal of specimens and contaminated material.

2. Incineration of disposable materials

Making an incinerator (Fig. 3.70)

An old metal drum is suitable for this purpose.

1. Fix a strong metal grating (G) firmly about one-third of the way up the drum.

2. Cut a wide opening or vent (V) below the level of the grating.

3. Find a removable lid (L) for the drum.

Using an incinerator

● At the end of each morning’s and each afternoon’s work, place all used stool and sputum boxes on the grating of the incinerator (Fig. 3.71).

|

Fig. 3.70 Components of an incinerator G: metal grating; L: lid; V: vent. |

Cleaning, disinfection and sterilization in the laboratory

1. Cleaning glassware and reusable syringes and needles

Instructions for cleaning:

— glass containers (Erlenmeyer flasks, beakers, test-tubes)

— pipettes

— microscope slides

— coverslips

— reusable syringes and needles.

Glass containers

New glassware

Glassware that has never been used may be slightly alkaline. In order to neutralize it:

● Prepare a bowl containing 3 litres of water and 60 ml of concentrated hydrochlo- ric acid (i.e. a 2% solution of acid).

● Leave the new glassware completely immersed in this solution for 24 hours.

● Rinse twice with ordinary water and once with demineralized water.

● Dry.

Dirty glassware

Preliminary rinsing

Rinse twice in cold or lukewarm water (never rinse bloodstained tubes in hot water).

If the glassware has been used for fluids containing protein, it should be rinsed immediately and then washed (never allow it to dry before rinsing).

Soaking in detergent solution

Prepare a bowl of water mixed with washing powder or liquid detergent. Put the rinsed glassware in the bowl and brush the inside of the containers with a test-tube brush (Fig. 3.57). Leave to soak for 2–3 hours.

Tuesday, January 6, 2015

Measurement and dispensing of liquids

Many of the liquids handled in the laboratory are either infectious, corrosive or poisonous. It is important for the prevention of accidents that the correct procedures for the measurement and dispensing of these liquids are clearly under- stood and are followed conscientiously.

Many of the new procedures for analysis require very small volumes of fluid and various pipetting and dispensing devices are available to enable small volumes to be measured with great precision.

Large volumes can be measured using a measuring cylinder or a volumetric flask. A measuring cylinder measures various volumes of fluid but is not very accurate. A volumetric flask measures a single volume of fluid, e.g. 1 litre, accurately.

Small volumes of fluid (0.1–10 ml) can be dispensed rapidly and accurately using one of the following methods:

● A fixed or variable volume dispenser attached to a reservoir made of glass or polypropylene. Various volumes from 0.1 to 1.0 ml and from 2.0 to 10.0 ml can be dispensed.

● A calibrated pipette with a rubber safety bulb.

1. Pipettes

Types of pipette

Graduated pipettes

Graduated pipettes have the following information marked at the top (Fig. 3.44):

— the total volume that can be measured;

— the volume between two consecutive graduation marks. There are two types of graduated pipette (Fig. 3.45):

● A pipette with graduations to the tip (A). The total volume that can be measured is contained between the 0 mark and the tip.

● A pipette with graduations not extending to the tip (B). The total volume is contained between the 0 mark and the last mark before the tip (this type is re- commended for quantitative chemical tests).

Various volumes can be measured using graduated pipettes. For example:

— a 10-ml pipette can be used to measure 8.5 ml;

— a 5-ml pipette can be used to measure 3.2 ml;

— a 1-ml pipette can be used to measure 0.6 ml.

|

| Fig. 3.44 A graduated pipette |

Monday, January 5, 2015

Hyponatraemia: assessment and management

Clinical assessment

Clinicians assessing a patient with hyponatraemia should ask themselves several questions.

- Am I dealing with dangerous (life-threatening) hyponatraemia?

- Am I dealing with water retention or sodium loss?

- How should I treat this patient?

To answer these questions, they must use the patient’s history, the findings from clinical examination, and the results of laboratory investigations. Each of these may provide valuable clues.

Hyponatraemia: pathophysiology

Hyponatraemia is defined as a serum sodium concentration below the reference interval of 133–146 mmol/ L. It is the electrolyte abnormality most frequently encountered in clinical biochemistry.

Development of hyponatraemia

The serum concentration of sodium is simply a ratio, of sodium (in millimoles) to water (in litres), and hyponatraemia can arise either because of loss of sodium ions or retention of water.

- Loss of sodium. Sodium is the main extracellular cation and plays a critical role in the maintenance of blood volume and pressure, by osmotically regulating the passive movement of water. Thus when significant sodium depletion occurs, water is lost with it, giving rise to the characteristic clinical signs associated with ECF compartment depletion. Primary sodium depletion should always be actively considered if only to be excluded; failure to do so can have fatal consequences.

- Water retention. Retention of water in the body compartments dilutes the constituents of the extracellular space including sodium, causing hyponatraemia. Water retention occurs much more frequently than sodium loss, and where there is no evidence of fluid loss from history or examination, water retention as the mechanism becomes a near-certainty.

Water retention

The causes of hyponatraemia due to water retention are shown in Figure 8.1.

|

| Fig 8.1 The causes of hyponatraemia |

Gram-Negative Bacilli

Asporogenous Gram-negative bacilli of clinical importance can be divided into two major groups. Glucose-fermenting, oxidase-negative, and catalase-positive members constitute one group, called Enterobacteriaceae. Several members of this group are normally present in human intestines and others are causal agents of serious infec- tions. The second group, somewhat more heterogeneous, usually called nonfermentative Gram-negative bacilli, are glucose nonfermenters. They are widely distributed in nature and prefer aquatic habitats. However, several members of this group are frequently isolated from human sources and known to cause serious infections. A simple and practical scheme for the grouping of important pathogenic Gram-negative bacteria is depicted at the end of the previous chapter.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)